In this article Agnese Pacciardi, PhD scholar in Political Science at Lund University and Joakim Berndtsson, researcher in Security Studies at Gothenburg University, analyse the start of a fully-fledged “migration industry” as a result of the European policy of externalisation in Libya.

Through the analysis of the project “Support to Integrated Border and Migration Management” funded by the European Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTFA) and implemented by the Italian Ministry of Interior, the article illustrates how the management of migration flows is delegated to a complex network of public and private actors which constitutes complex governance structures. In an extremely unstable context like the Libyan one, where human rights are systematically violated, the externalisation of borders and security raises worrying issues of transparency, accountability and political, legal, and moral responsibility of the European Union and Italy.

Thanks to several freedom of information requests to the European Commission and the Italian Ministry of Interior, this study sheds a light on some of the mechanisms and logics underlying externalisation policies. As public and private subjects are more and more involved in the management of migration flows through Italian and European funds, it is essential to know these actors,discover which relationships they have and analyse their role in border control. Answering these questions means understanding the political implications of migration management practices in third countries.

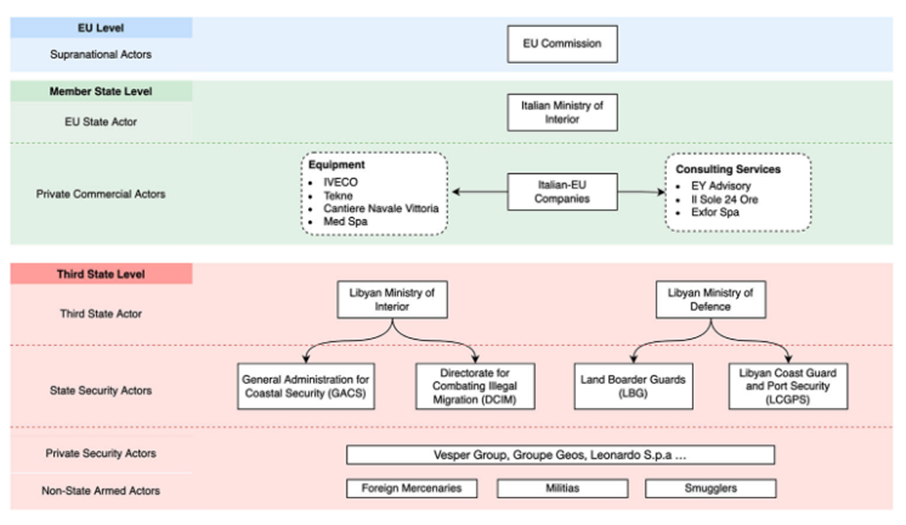

Through their analysis, Pacciardi and Berndtsson illustrate how the European Union delegates the external border control both to Italian security and consultancy companies, and to Libyan state actors (in particular to the border police). The latter are closely linked to non-state actors (including foreign mercenaries) and different armed groups. The migration industry that comes out is therefore a hybrid between public and private, state and non-state, domestic and foreign.

The externalisation of border and security – the authors conclude – generates semi- autonomous dynamics. For these reasons, assigning responsibility for the outcomes of these policies to supranational actors (EU), state actors (Libya, Italy) or non-state actors (private companies, traffickers, militias, mercenaries, etc.) is extremely complex. Moreover, by mobilizing a large amount of funds, these policies create a large demand of security services for the benefit of the Italian and European private sector, as well as for the Libyan authorities, traffickers and militia. Finally, the study confirms the difficulty for civil society to scrutinise these projects, confirming how opacity and complexity are deliberately at the basis of instruments such as the European Emergency Trust Fund for Africa.